Review of Runge's "Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament" Pt 4

Before moving on to review Chapter 2 of Part 1 of Runge’s

Discourse Grammar, I want to reiterate a thing or two. First of all, if you have not read the

previous parts of this review series, I would highly encourage you to. In those reviews and the comment sections

accompanying them, I explain the vantage point from which I am approaching

Runge’s work, namely, more as a teacher in the church and less as a

linguist! As I have shown, the preface

and subtitle of Runge’s book explicitly state that coming at this grammar from

such a stance is not only fitting, but expected. Indeed, the following video is another place

that explicitly states that this is aimed at pastors, preachers and church

teachers, not simply linguists. Thus, I

am asking questions that a normal pastor or preacher might ask!

Another matter I would like to address, which Runge himself

and Mike Aburey have drawn attention to is the fact that I may be conflating

the terms Discourse Grammar and Discourse Analysis. Where I have seen the lines between these two

things as somewhat blurry, they want to draw sharp distinctions. This is fair, to be sure! Having said that, however, I do want to

suggest that if these matters are blurry to me, the book might do well to

clarify this in the preface or introduction because it might well be blurry to

others also. Furthermore, as I have

stated in the comments section of Part 3, many of the questions I have raised

thus far, particularly those having to do with Discourse Analysis (DA), are indeed

related to the contents of the Discourse Grammar (DG). This is not to say, however, that the two are

the same or that they are mutually exclusive.

For me, the two are indeed connected. Again, if this is a major point of

contention, perhaps some clarification is needed at the front part of the

book. This is not a critique as much as

it is a suggestion. I cannot imagine a

scholar writing an Introduction to the New Testament and then suggesting that

it purposefully and wholly be separated from the New Testament itself.

Moving on, we find ourselves at Chapter 2 of Part 1, a

chapter titled “Connecting Propositions”.

The aim of this chapter is to provide “a very basic overview of the

different sorts of relations that can be communicated by the most commonly used

NT Greek connectives” (17). Runge opts

to use “connective” in place of the traditional “conjunction” because “languages

commonly use forms other than conjunctions to perform the task of connecting

clause elements” (17). More

specifically, Runge reviews 9 “connectives” which, each in their own right,

“play a functional role” in the NT’s discourse “by indicating how the writer

intended one clause to relate to another” (18).

Here, I will survey Runge’s overview of the first four of these terms

and offer some thoughts of my own along the way as well. In Pt. 5 of this series, I will review the remaining 5 connectives.

One of the most interesting and insightful aspects of this

chapter has to do with Runge’s non-traditional approach. Whereas folks like Daniel Wallace have tended

map or match Greek conjunctions to English counterparts, in other words, taking

a logical approach where one word equals another in a certain context (e.g.

ascensive kai, = even, connective kai, = and, also, etc.), Runge’s functional

approach, less dependent upon using English grammar as its baseline, suggests

that there may be a unifying function that each connective performs (18). It is more helpful to understand how each

connective differs “based on the function that it accomplishes in Greek” than

to simply know “how to translate” them (19).

To put it differently, the goal is exegesis, not simply translation;

unlike translation, exegesis allows for the elaboration of various “aspects of

a passage,” even and especially those that “cannot be well-captured in

translation” (19).

Following Behagel’s Law, which asserts that “items that

belong together are grouped together syntactically” (19), Runge contends that

connectives serve the role of specifying the “kind of relationship” between

each of these items (19). He begins with

asyndeton, the grammatical concept which refers to “the linking of clauses or

clause components without the use of a conjunction” (20). Runge signals this feature with the ∅ symbol. A helpful way to think of conjunctions is to

think of them as constraining elements.

In other words, they constrain or limit the relationship between clauses

or clausal elements. For example, I

could say “I laughed and cried” or “I laughed then cried” or “I laughed but cried

too”. In the first instance, laughing

and crying are taken together, as happening at or around the same time; this is

denoted by the word “and”. In the second

instance, “then” denotes sequentiality as the crying comes after the laughing. In the third instance, the word but (modified

by “also”) denotes contrast where, on the one hand I laughed, and on the other

hand, I cried. In each instance, the

connecting words “and,” “then” and “but” help make logical connections between

two actions. However, I could just say, “I

laughed. I cried.” Note here, that there is no connecting word

such as “and” or “then” between these two actions/sentences. Even so, as a reader, you make a connection

between the two. The act of connecting

clauses or clausal elements in this way is called asyndeton. Using Runge’s method, we would employ the ∅ marking to signal asyndeton: “I laughed. ∅

I cried.” It might have been beneficial to have more

written on how to recognize asyndeton.

For example, can asyendeton be recognized through repetition (of stem,

person, number, case), parallelism, word order, etc.? Beyond the absence of a connective, are other

ways of recognizing asyndeton?

Seamlessly, Runge moves from discussing asyndeton to kai,.

The most frequent word in the New Testament, this term is usually glossed

as “and, even, also”. That seems

straight forward enough. However, Runge

suggests that this seemingly simple and familiar term actually serves the purpose

of signaling an intimate link to what comes before it. In other words, it is not simply a “connective”

(and) or “adversative” (but), rather, it is a word that links together “items

of equal status” (23-24). This also

means that it has no inherent judgment to make “regarding semantic continuity

or discontinuity” (24) but constrains such “elements to be more closely related

to one another than those joined by ∅”

(26). Further, if an author switches

from kai,, particularly in a narrative, it should

signal to readers/hearers that “a new development” is taking place, such as a

transition to or from background information (26). This nuance is certainly helpful. Still, I would have liked for Runge to

articulate, just a bit more, what he means by “status” in the phrase “equal

status”. Does this refer to time, kind,

grammar, syntax, meaning, etc.? It seems

as though it would refer to equal syntactical status, that is, equal status

within the clause, sentence, etc. itself.

However, Runge may have meant something different by this.

If the conjunction kai, signals intimacy between two elements (e.g.

clauses, phrases, etc.), which denotes their “equal status” then for Runge, de, functions as discourse marker of

development. Sitting kai, and de, side-by-side,

Runge marks kai, with (-) and de,

with

(+) symbolizing either no development or new development. As Runge says, “For speakers of English,

development is a very difficult concept to grasp. It is natural to conceive of temporal

development, as in a sequence of events, but challenging to conceptualize

logical development when it does not involve sequence” (36). Here, Runge has hit the nail on the

head! It is, perhaps, even more

difficult for those of us who have had kai, =

and/even/also or de, = but/and ingrained in us, to begin thinking about how these terms might take on new force. I must admit, I had to read this section of

Runge’s discussion more than once to really get what he was suggesting.

Drawing on Levinsohn, Runge uses the concept

of “chunking” as a way of understanding the function of de, (30).

Basically, chunking is breaking portions of a discourse down from larger

to smaller chunks. I might say that it’s

the difference between attempting to eat an entire, unsliced or uncut turkey on

Thanksgiving and slicing or shaving it up, so as to have smaller, more

manageable chunks to consume. Taking

this gross analogy a bit further, we could even depict de, as the knife that cuts the discourse into

smaller chunks. Furthermore, each new cut

or slice, each new de,, marks

a new development. Here is an example,

where de, marks a new development (+) and kai, marks no development (-):

I laughed. ∅ I

cried. ∅ I sang. ∅ I

went to the store. ∅ I danced. ∅

I

jumped.

|

I laughed de, I

cried. (I laughed +then I cried.)

De, I

sang kai, I

went to the store. (+Then I sang -and I went to the

store.)

De, I

spent money kai, I

went home. (+Then I danced -and

I jumped.)

|

It is helpful to contrast kai,

and de, to make sense of what is going

on here. You can see above, that in the

first column, we practically have a list (Runge does something similar in his

grammar) but I wanted to offer my own example with his symbols included (which

Runge does not do at this point in the grammar). In the list-like example, you can see that

the ideas are connected only through asyndeton, that is, they are logically

connected as they appear together and if you wanted, you might even try to read

them sequentially, however, the context does not suggest that they had to

happen in this order or even in the same day.

They are mere statements about things I did at some point or

another. They are connected logically, by

way of being mentioned together, but not sequentially.

That all changes in the second column. Here asyndeton is not used. Instead, explicit connectives are used. Furthermore, you can see how the connectives

denote explicit developments, or not, by way of using kai, or de,. Where kai, is used, there are no new developments;

the kai, is, instead, functioning to

relate the clausal elements equally or revealing their equal status. The de,

on the other hand, is marking a new development. To put it differently, where a de, appears, we have new chunks or

slices. Thus, in each line, we have a

new chunk or development, which is denoted by de,. This perspective that Runge offers, while

challenging to wrap one’s mind around at first, is really valuable once

grasped. It allows us to follow the discourse

in a new way and discern whether and where new developments may be taking place

or not. The initial payoff may seem

minimal but in all reality, the final dividends may prove incredibly rich.

This leads us to review the fourth discourse grammar

element, the narrative to,te, which “can

fulfill the same role as a connective in contexts where none are present”

(especially Mt and Acts) (37). The role

of to,te is not to tell one about a

specific amount of time that has passed but rather, that sequentiality is in

view and as such, a new development has occurred. This is not too far from the discussion above

about de,. So, how is it that “they differ from one

another?” (38) Runge suggests that while δέ is the “default development marker” it does not “specify the exact nature of

the development” (38). To,te, however, “makes explicit that the

development that follows is temporal in nature” whether that temporality is

generic or not (38). To clarify, to,te is a “low-level break in the text”

which marks a new development but does not lead the reader to believe that a

whole new topic is in view! Just as

well, the segmenting effect of to,te has

the capability of attracting emphasis or attention. Runge gives some excellent examples of this.

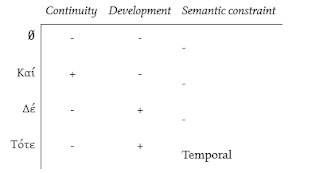

In closing, let me give a quote from Runge as well as a

snapshot of a table or chart which features the connectives and their

functions, as described thus far (42):

“So far we have

looked at two kinds of connective relationships: indicating the continuity of

two joined elements (∅ versus καί), and signaling whether

what follows represents the next step or development of what precedes (δέ and τότε).”

As a teacher and student of languages, I have found that it

is often the shortest words that pack the most punch or carry the most

force. It is so easy to focus on the “theological

words” or the big words at the exclusion of the short words. Runge’s discussion thus far has not only

reminded me of this but has helped me look at Greek differently, forcing me to

pay extra close attention to these tiny connectives. The further I get into Runge’s work, the more

I become convinced of the fact that such an approach is incredibly valuable for

those studying the New Testament. So,

head on over to Logos and pick up your copy of Runge’s work, I don’t think for

a second that you’ll regret it!